Not To Disappear is the second album released by Daughter, and features the three singles ‘Doing The Right Thing’, ‘Numbers’ and ‘How’. In collaboration with the BAFTA-nominated Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, and writer Stuart Evers, the band released three respective short films for the tracks. Though all are linked by one motif, the films can be enjoyed on their own or sequentially.

You can read about the experiences of all involved, the meaning behind the stories that inspired the films, and find-behind the-scenes photos from the video shoots below, along with the music videos themselves.

We love this band. They quietly remind us why music really matters.

We’ve worked together since the first video from ’If You Leave’. And when the early demos of ‘Not to Disappear’ started coming out of the studio it was obvious they were setting the bar exceptionally high for this new album.

The challenge was laid down, and we also wanted to be ambitious in our approach to making a series of videos for the new tracks. Each film, we decided, would focus on the obsessive world of an individual character. And although the films wouldn't be linked explicitly, each would - in a sense - pass on a baton to the next.

To begin, we commissioned three short stories by one of our favourite young authors, Stuart Evers. We then adapted these into a trilogy of interwoven films; all shot on the Kent coast in one shoot before the band headed off on tour. A different actor leads each one: Richard Syms, Natasha O’Keeffe and Marama Corlett. There's also faces that reoccur and, for the eagle-eyed, a few sly references to Daughter’s past.

We invited Paul Heartfield, a photographer we've long admired, to document the process. Within these pages you'll find a selection of Paul's images as well as Stuart's original stories. If you listen carefully, you might just hear someone, somewhere, listening to 'Not To Disappear'.

Thank you, Daughter, for reminding us again that music really matters.

Iain and Jane

Directors

Story • Watch

DRESS

Some days his feet furious; some days soundless. The boots’ surprising shine; the fast/slow click of their unexpected heel. Through the streets, left and right, boot and heel. Between the high-rise and low terrace, clack, clack. Boot and heel; leather upper, leather sole.

Those are some lovely boots, you got there – Handmade, love – They look it, too – Uncle’s a cobbler, does ’em in his spare time. Last forever, boots as good as these – You’ll walk a lot of miles in them, ye will – Yes, love – Can’t dance in ‘em though, can ye? – No, love, different shoes for dancing. Winkles for dancing – Ye a dandy, so you are. – I just like the best, love – And that’s why you like me? – Might be, love. Might be.

Through the streets, left and right, boot and heel. A hunch in his shoulder, pinch at the nape. The same raincoat, in all weathers; one of three suits. This day, the steel grey; three-button, easy drop, turn-up in the trousers. The elasticated sides of the boots once just visible; now, with age, him losing length in the leg, the cuffs covering. This suit he chalked himself, cut himself, stitched himself. Lasting. Suits like that. Lasting. He wears one every day. This day, every day.

Ye make me feel dowdy in your suits. Ye so sharp and what have I got? Rags, so they are, rags – You look beautiful in that frock – It’s rags. All of them rags. They look at you, not me. Look at ye suits and pity my dress – They do no such, love.

Every day, click the lock and walk. Click the lock and walk the half mile. A straight road. Through the streets, left and right, boot and heel. Between the high-rise and low terrace, clack, clack. A straight road from home to destination. Sometimes hands in pockets, sometimes hands behind his back, a slow whistle on his lips. He looks at the walkway, the brick and asphalt. Boot and heel, boot and heel. People pass him by. He passes them by. Passes chicken shops. Passes betting shops. Passes off licences. Passes by.

I only let ye cause you bought me my dress – I know, love – I would have done anyway, but not so soon – I know, but it looks good on you, good off you too – Never had anything like it. Makes me feel like a queen, ye know. Like a Gypsy princess – One day you’ll have a wardrobe full of ’em – And we’ll dance every night, yes? – Every night, love.

A strip of stores and there he stops. Push open the door. The drycleaner is a man on the phone. Always on the phone, forever on the phone. The drycleaner turns to the rack on his left. A red dress in plastic sheath. Ruffles and sequins. He places it on the counter and puts out a hand. Crossed palm with a note. They do not talk. He talks on the phone. He picks up the dress and holds it by the hanger. He leaves the shop and is on the street, between high rise and low terrace, a dress blowing in the wind, held by a crook of finger.

For luck, love – But always that dress? – Ye bought it for me – I bought you lots of dresses, you’ve bought yourself – I know, but this was the first I ever had, first of my own – But you have others – You mean less – I mean that you don’t – It makes me feel like a Gypsy princess – It’s just – Just what? – Never mind, wear the dress – Ye couldn’t tell me not to.

People pass by and some look at the dress, the almost companion. Some have seen him many times before, others not at all. Under the plastic, the dress writhes in the wind. Between the high-rise and low terrace, clack, clack. Boot and heel; leather upper, leather sole. The dress in hand. He takes the stairs, up to the flat. The door gives heavy, the hallway with its smell of her. There is the suitcase, already packed. Bedwear mostly, things in which to sleep, a box with a mug she won’t be able to use, a glass likewise.

It’s just a setback, we’ll be – No. I tell ye, shush ye, we know, love – It’s nothing, we all get, as we get older, we – shush ye, ye know as well as I. You can put it away, the dress, the shoes too – you can’t be giving up now, Doll – I can give up whenever I want, my love. And it don’t matter if I do or not. There’ll be no more dancing – There’s always dancing, Doll – Keep your dreaming head on, Harry.

The dress goes into the empty closet. He likes the clinging static of the plastic around the fabric. How he has held that dress, how he has held her wearing that dress. She makes a noise, kittenish the tumble from her, a dribble, and yet he turns. She is sitting on the edge of the bed, neck craned. She does not look at him. Looks around as though she does not quite yet remember where she is. There are boxes on the floor. There are spaces on the walls where rectangular things once were. Pictures. Paintings. There are many more. On every counter top, on every dressing table, photographs, mementos.

He picks up a picture of the two of them, oh that evening. At the dancehall, in their youth, and the way he sweat so much from the dancing and the way her make-up held despite the heat and he holds the picture in his hands and smiles and holds it up to her.

‘This one, yes?’ he says and he’s away and talking of the past as he puts it in the tea-chest. A picture next of her mother, a pink cloud, a candy-floss monster woman, and then the kids, the two of them, so pink and young, the older so much older. With rolled pieces of paper, with little kids of their own, with golden drinks beside candlelit foreign bars. He places them all in the boxes; she says nothing, does not acknowledge the photos. The frames. The last thing a statuette, two dancers on the top. He does not cry. He holds it like they have won it again, and she does not flicker. Just stays on the edge of the bed, eyes for the window.

It’s a beautiful place – … – Don’t you think? – … – they can look after. Better than me, doctors and nurses and all that. And there’s always somewhere – … – Talk to me, girl – … – Tell me, Doll – … – Tell me this is the right thing – … – Tell me.

On her bedside is a distillery of pills, a little industrial complex. Beyond them, her husband in his youth. She picks up the photograph and the pills crash to the floor. She holds him in her hands and he comes to sit next to her. She puts her hands on his lap. He brushes her hair. He brushes her hair the way he used to before they danced.

The boxes are full, the room, their room is empty. One thing he has kept for himself is on her dressing table. The picture he could not part with. It is of them dancing and he takes the boxes from the room to the hall. At the last one she stands and heads towards the closet.

He uses the telephone in the hallway, the taxi to take them. A life in three boxes, one suitcase. There are pictures on the wall too. Some missing again. More children, more dresses, more history. He feels the weight of it, heavier than the boxes, so much heavier.

When the call is done he replaces the receiver. The car will be there, quickly, without thought or reverence. And then she is there. In her red dress, smiling. She puts out her hand. He takes it. They waltz in the hallway. Waltz and they wait for the taxi to take them to the dancehall. The dancehall, yes. To dance.

Story • Watch

WINDOW

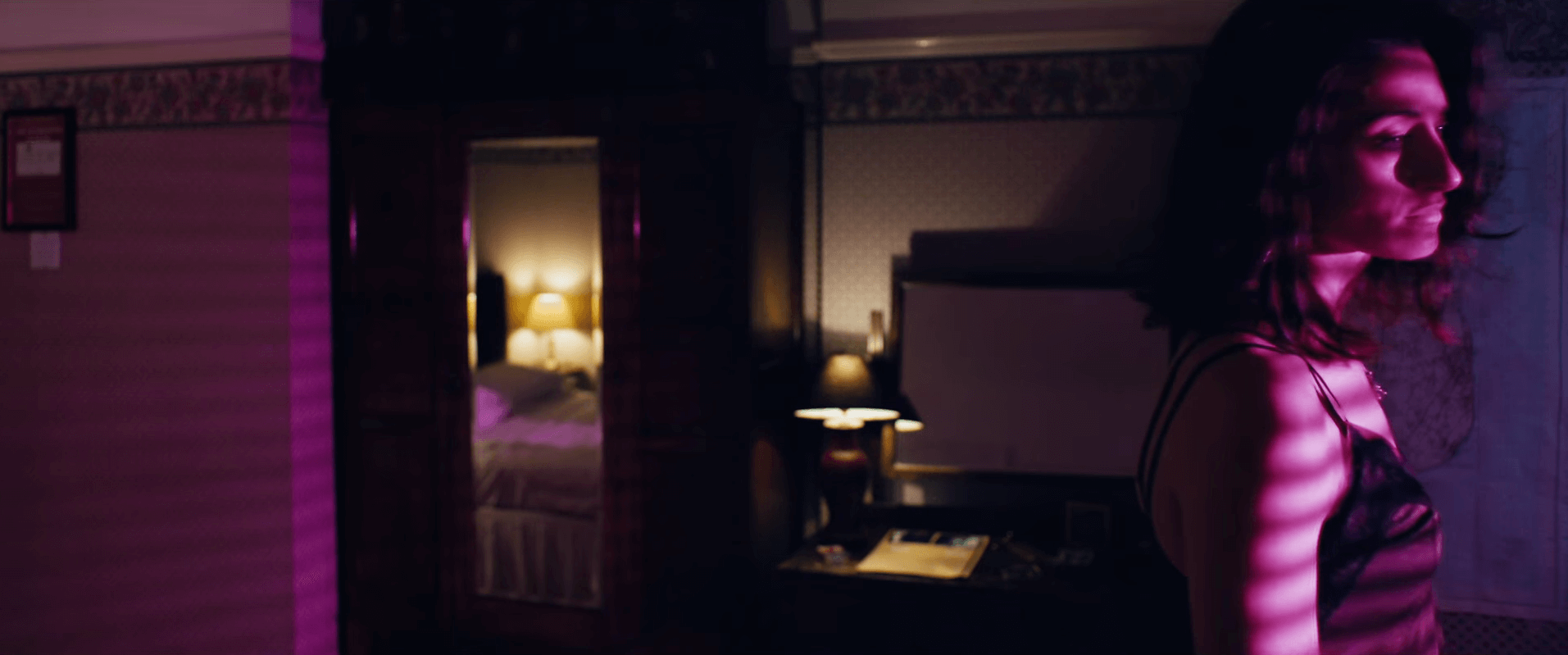

The light through the blinds is neon and video flicker. It stutters over her body, pale blue and red. On the bed she breathes so slowly, so thinly; awake, but eyes closed, resting. She crosses and uncrosses her legs, opens her eyes. She sees the cracks in the ceiling, its spindly fissures. She puts one hand over her left eye, then one over her right. She can still see the neon. She can still feel the video flicker.

There is no clock to be seen from the bed, so she moves her torso bolt straight, as though woken suddenly in the night. The room is small. There is a desk and a wardrobe, no lights are lit. She rubs her legs and looks at the desk, at what is above its top. She cannot remember whether this was here before, or whether she brought it herself.

She takes the desk seat. It is functional rather than comfortable, it feels cool against her thighs. There is a file on the table, and tacked to the wall is a map.

The report is typed in old-fashioned ink, bound in manilla, a photograph of two men paperclipped to its front. She opens it, flicks through, but it tells her nothing she does not know in more intimate, more exacting deatil. She looks at the map tacked to the noticeboard. She knows the places. There are pins and routes, but she knows them better than that. She traces a line with her fingers.

On the table, behind the file is a deck of cards and two silver coins. She moves the file to the side of the desk and deals herself two hands of seven cards. Alternating between hands, she turns each one over, until the winning cards – those on the left – have revealed themselves. They are all picture cards. She puts the cards back in the pack and takes the coins. She stands – illuminated and then not, lit again then not – and flips the first coin. It comes down on her hand as heads. She stands and flips the second coin. She closes her eyes and opens them. It is heads.

On the desk is a clock. She picks it up, checks the time and takes the cards out one more times. She only deals the top card. It is an ace. She flips one of the coins. It is heads. She rolls her neck and shoulders. She walks to the wardrobe and opens it. Inside is a red dress in a plastic sheath. Below it is a small bag and a pair of shoes.

*

Under neon and video flicker she walks the dark. A preacher is preaching from a soapbox, crazed eyes and megaphoned. He preaches and she stops to listen. The preacher seems to pause, but does not lose his beat. He is talking about salvation and damnation, about the Lord and the Devil and how the Devil seems closer to this world than the Lord, does it not feel that way, sister? Does it not feel like God has abandoned us all and the devil is here to soothe us and tempt us, does it not, sister? But I am here to say, sister, that God is here and God is now and he is closer at hand than ever, and we shall know him and know his face soon enough. She smiles. She smiles and spits on his shoes. The preacher does not see, or does not notice, and keeps up his preaching.

Under neon and video flicker she walks the dark. A man in sportswear calls to her, tries to put his hands on her waist. She pauses and his hands do not connect with her, but she stands on his shoelaces, and he falls to the floor, heavily, and with a yowl. She ducks between a couple and a group of friends as though never there.

She turns to look, to confirm the man in sportswear has not followed her and collides with two immediately incensed women. They point at her, shove her, but she only smiles. The two women stop. The two women do not continue their pointing, their shoving. They become quiet when they see the dress.

At the junction, a man shouts at her from inside a large car. He has his arms outside the window, he beckons her over, honks his horn. She lights a cigarette and flicks her match in his direction. The car begins to flame from the inside, the man trying to put out his smoking crotch.

She turns left and the road is fat with people, light from bars, from streetlamp halos. She stands and watches the throng. She throws her cigarette to the floor, crushes it under her heel. Someone jolts her as they walk past and she watches them trip on a raised pavement slab.

The bar has outside seating and on one of the tables one of the men from the reports is drinking with two women and another man. She narrows her eyes and watches him talk animatedly about something; the man and women listening intently. His arm movements are wide and rangy. They are hanging on his words. Then his words stop.

His words stop and they watch as he retches and violently expels what looks like his whole guts from his mouth. The man and woman are terrified. The blood is on their clothes and on the table. She watches. She watches them all, then hails a taxi.

She gives the cab driver a slip of paper on which she has written an address. They drive and for the journey, the taxi driver is a mouth in the rear-view mirror, constantly moving. She looks out of the window, she looks anywhere but at his mouth moving, those things he is saying.

The city looks kinetic from the back of the taxi; the lights, the people, the buildings stretching to the stars. She peers out the window like a tourist, like she does not know these streets, these people. The taxi stops. She pays the driver and walks towards the bar, his mouth still moving, still talking.

At the junction there are two preachers. A man and a woman. They have loudhailers and the woman is giving out fliers, which die as confetti on the pavement. She listens to the two preachers: we are bound to the realms of hell without our saviour Jesus Christ and I know that he is here with us now, don’t you feel him, sister? At this, she just laughs.

Inside the bar, a band is playing. She watches them for a moment, then looks around the sparse audience. She sees the man from the files. He is sitting alone, a glass of whiskey in front of him. He looks up and sees her. He shakes his head as she sits down in front of him. He smiles and takes a drink. He is about to speak, but cannot speak. Slowly he slides down his chair, a thin line of blood at the corner of his mouth, spilling down his chin, his shirt and onto the table. She blows him a kiss, then leaves the bar. Outside there is the preacher. She ignores him and hails a taxi.

*

The light through the blinds is neon and video flicker. She places the dress in its plastic sheath. She takes off the shoes and opens the wardrobe. There is a shirt and a pair of black trousers hanging, a small bag and a pair of flat shoes. She removes them, and replaces them with the dress, bag and shoes.

Dressed, she opens the door and closes it behind her. The light through the blinds is neon and video flicker as she kicks the keys under the door. A woman walks towards her. They pass in the corridor and do not speak. They do not even look at each other.

Story • Watch

5,040

The door came with a mortice, a Yale and a chain. To these she added two deadbolts. Black, heavy: one low, one high. The symmetry was pleasing. She removed the single chain and replaced it with a pair. One under the higher bolt; the other above the lower. The symmetry was maddening. She added another mortice, quarter of the way up from the foot of the door. She did not add a peephole. She thought about it; but worried it would impact the structural integrity of the wood. So seven locks. Seven locks and a wooden door. She dreams now of metal doors; of five-hook systems, anti-lift bolts, auto-locking centre latches; 70mm fully-welded chamfered composite outer-frames. Doors the catalogues describe as Police Approved.

There are 5,040 different permutations; but in effect there are only two: locked or unlocked. How many permutations has she reached, looking at the door, sliding a bolt, turning a key, rattling a chain? Perhaps all. Perhaps just in the low hundreds. She does not keep a tally. It does not occur to her, standing at the door, saying yes with a left-turn, no with a right. Yes/no. Open/close. Safe/Unsafe.

She has a bed. A couch. A radio. A bathroom and kitchen. But really only the door. The windows have bars. When she opens the curtains, rarely, she sees their black rails, their spiked tops, a rusted pair of padlocked chains binding them. These do not concern her. There is a wall beyond them, close and that wall is high and has bottle shards – winebottle green; pillbottle brown; milkbottle clear – set into its summit. Some days a cat chances it; most often he knows better.

She has a window, but really she only has a door. Sometimes she takes an old chair, rented like the whole room, and sits by it. She opens a lock and says yes; locks one and says no. Some days she is quick, some days slow. Sometimes deliberate, others wild. Each day by the door. All day, sometimes.

Each day, between three and three-fifteen, her landlord comes with the things she has ordered. For this she pays him an extra fifty a month. He does not care. She leaves the chains and bolts off, and locks herself in the bathroom. She waits. He opens the doors and puts down the goods: the food and drink and catalogues. He locks up and knocks three times to tell her he has gone. She comes out and there is food. There is no man. She hunts the flat for him, but he is not there. She pulls the bolts, affixes the chains and takes a bottle of wine from the bag, drinks it from the bottle. She sits on her chair by the door. She opens the top locks and moves the lower ones. She unlocks a mortice. No. Locks it back. Locks them all again. There are 5,040 different permutations; but in effect there are only two: locked or unlocked.

Of the permutations the most feared is the all but unlocked; just the Yale, the centre of the door, the central lock. Undo the deadlock. Turn to the right. Yes. Open now. Open. No. Push back. Push back. Slam bolts, turn keys, lash chains. Almost yes. Almost. Open for that moment. Open. Closed now and locked.

She starts at the bottom, works her way up and then back to that moment. Unclasp the dead lock. Turn to the right. Yes. And the door is cracked open. Pulled open. A thin sliver, like the glass shards on the wall’s summit. Open more. Pavement and road and railings and sky. Early morning light, must be early morning. No sound. No cars. No traffic on the road. There is no wind. Everything still. On the rack is the set of keys, bunched. So many there. She takes the keys and closes the door behind her. There is no one around. She shields her eyes, but still no one. She steps down, one two. She is on the pavement. She walks slowly. She walks and crosses the road. The plants and trees nod to her, no one else. She can see the frosted tops of waves. How much she has missed them. She walks along the promenade, sunlight-drenched and pale. Her pace quickens and soon she runs. Lactic in her thighs, but nothing bad, nothing so bad. She runs and stops by the ramp to the beach. The empty beach and empty streets. She puts her hands on her hips. This is as before. This is how it was.

Down to the beach, down, down. Shingle and stone. Kicks off her shoes, leaves them in the stone. The wind is whips. Her hair makes hands, fingers in the gusts. She walks the sand, wet, to the water and weeps. She lets the surf kiss her feet, nurse at her toes. Birds in the sea air, light on the dips and curls of sea. If these are tears, they are of joy. Defiance. But tears, yes. On her cheeks and unbrushed away. She makes a noise. A rush from lungs and mouth. She does not pace forward nor back, but bellows into the wind, excited eyed, astonished by the water, the sky, the sand and stones beneath her feet.

These things do not last. They cannot last. She turns from the sea. She no longer knows where is home. The sea is simple, the town full: houses and roads and her footprints in the wet sand. She follows them back, ignores her shoes, back on to the esplanade, up and not knowing whether left or right, left or right. She closes her eyes and opens them. She is still here. Not at home. Not dreaming. Still here. Closes her eyes. Still here. A front door opens. Out steps a woman in a red dress. The woman walks towards her, she turns away.

She turns left and a woman in a red dress gets out of a red car. A car drives past, driven by a woman in a red dress. A woman in a red dress walks along the promenade with a dog. A woman feeds the parking meter wearing a red dress. The road becomes full of women in red dresses, talking on telephones, eating sandwiches, drinking coffee. She walks past them and they look at her. Down at her. Their looks multiply, they hum. And she wants to get back. Wants to find her door. In her hand she has keys, a heavy clutch of them. She walks, looking for the door. The door with the locks, its 5,040 different permutations. The women in the red dress look at her, she runs and ducks but they look at her everywhere. They look and look and she thinks only of the door. The door with its seven locks.

And there it is. Closed and safe. She opens the door with the keys, with shaking hands. Opens it and closes. Locks all the locks, bolts all the bolts, draws all the chains. She leans against the door and cries. Put her hands against its thick protection.

On her haunches she stays eyes closed. She opens them. On her bed there is something. She can see it, in cellophane wrap. She gets to her feet and to her bed. The dress, the red dress, is laid out. Freshly laundered. Freshly cleaned. It lies there as surely as herself.

As a film-maker how did you approach the idea of a trilogy of interlinked music videos?

When we all started talking about the idea of shooting more than one video it made sense to make them as parts of a series. The idea was for them to work in the same way the songs belong to the series of the album, and the album structure brings about links between the songs. We wanted to make films that, although independent of each other, had links. That’s when we brought Stuart Evers, the writer, on board. We gave him a few thoughts on how those links might work, but ultimately left it to him to figure out. Some of the links between the films are more obvious than others, but of course the motif of the red dress is the strongest thread that runs across all three stories and films.

Tell us a little about your relationship with Stuart Evers and the creation of the three short stories from which the trilogy is based?

Stuart is a old friend. When we first left art school we had part-time jobs in different bookshops. Iain was at the same branch of Waterstones as Stuart. Since then Stuart has gone on to be a hugely respected author, and something of a master of the short story. More often than not music videos don’t have scripts, the ideas are sketched out more loosely. We really wanted to work with a writer and to take the ideas from short stories, then into scripts, then onto the screen with the music. We thought this process could bring something interesting to the trilogy.

What were you looking for in each individual narrative’s central character?

The band were keen on the idea of each story having one distinct central character that we stay with throughout the film. We all loved the idea of connecting the stories loosely to one another. We wanted three very distinct characters that would also be interesting for actors to play. Once Stuart began writing we were able to spend time thinking about these three individuals and how we thought they would look and behave. To be able to create a strong sense of character without a single word of dialogue was a real challenge. We were incredibly lucky to be able to work with Richard, Natasha and Marama, who are all wonderful actors.

How did you approach the task of tackling the subject matter of ‘Doing The Right Thing’?

It was incredibly moving to hear Elena talk about what inspired the lyrics, it’s a tough subject that the band approach with great sensitivity and understanding. Our family has been affected by dementia recently too. It can bring about a defiant resilience in those around it. Working with Stuart’s story we wanted to get that sense of how holding onto memories, souvenirs and routines can help to anchor a relationship with the person you can’t help but feel you’re losing.

There are some beautiful and subtle references to Daughter’s past. Are you surprised at how quickly fans spotted them after the launch of each video?

Not at all! We’ve seen enough Daughter shows to know that their fans are an incredibly committed bunch. That’s really what these references were about - we knew fans would watch the films several times, so we wanted to have some fun and give them some things to look out for. We’ve not followed closely enough to know whether they’ve all been spotted yet, but there were a couple of really subtle ones in there that may still be undiscovered! There’s also a lovely language of references between each of the films, people re-appear in different roles - look at the dry cleaner in DTRT and the barman in Numbers. The girls in red dresses in How, appear on the street in Bunny ears or in the bar in Numbers. Has anyone spotted that some of the paper birds from the Air session we did with the band are hanging in the girl’s bedroom in How?

There’s been much talk online as to the meaning of the Red Dress within the three films. Do you have your take?

We treat it like a baton being passed from one story to the other. We’d asked Stuart for one repeating element - something undeniably recognisable, shared by each story, but shifting in how it operates for each character. Ask Stuart, we’re sure he has the best understanding of how it works… We often talked about it as the somehow representing the past in DTRT, the future in How and the present in Numbers.

You previously worked with Elena, Igor & Remi on the video for ’Still’ and their beautiful ‘Live @ Air’ series - how do you find working with them? It seems a very trusting relationship.

We love this band, and we love working with them. They have a great chemistry between them, they’re open-minded and incredibly articulate through their music. When we made the video for ‘Still’ together it was a new experience for them, so we did our very best to make it as painless and creative as possible. We’ve worked with a lot of bands, and the process of making music videos is rarely enjoyable for anyone. But we get on well with Elena, Igor and Remi, and there is a trust between us that makes the process easier for us all. Live at Air was fantastic - we’ve shot a lot of live sessions with bands over the years, and the atmosphere at Air is always magical. It’s such a special studio, with an incredible history. To be able to capture those unique arrangements with the youth orchestra in such a perfect setting was a real joy.

Is there a shot or a scene across the three videos that you are most proud of?

Tough question! The biggest challenge was to shoot so much in a very short space of time, with a limited budget and on location in Margate and Ramsgate. The whole cast and crew worked incredibly hard to make that possible, and without their commitment the films could never have happened. So that’s what we’re most proud of - the collective energy and drive that got these stories from the page to the screen. There’s usually one shot when we’re filming that confirms that the ideas are working, the performance is right and the film is on the right track. With these it was seeing Marama on the beach about to run, seeing Natasha standing at the window in the pink and blue light and seeing Richard sat on the bench crying. We have some incredible footage of Elena singing on the set of each video - you only see small moments of this on the TV in DTRT. Maybe one day Elena will let us show you something else!

What's next for Iain & Jane?

Right now we’re working on a series for Sky Arts based on short stories by Neil Gaiman called ‘Likely Stories’. They’ll be on air later at the end of May. We also released a drama on BBC Two on 17th March. It’s called Murder: The Big Bang, and is still available on iPlayer for a couple of weeks. In the longer term, we’re working on our next film and a couple of new art projects.

Join the mailing list for your chance to win a special edition booklet about 3 Films

Director: Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard

Writer: Stuart Evers

Photographer: Paul Heartfield

Harry: Richard Syms

Sam: Natasha O'Keeffe

Ava: Marama Corlett

Producer: Vanessa Farinha

Director of Photography: Chloë Thompson

Editor: Rachel Spann

Casting Director: Layla Merrick-Wolf

Art Director: Cara Barry

Production Stylist: Sal Pittman

Hair & Make-up: Martina Luisetti

Screenplays: Cara Barry

Focus Puller: Emil Davidov

Steadicam Operator: Matthew Allsop

2nd Assistant Camera: Howard Mills

DIT: Joe Lovelock

Gaffer: Harry Gay

Spark: Hugh Donnelly

Grip: Ian Ogden

Grip Assistant: Adam Zimmerman

Sound Recordist: Helen Miles

Art Assistant: Lucy Baker

Runners: Maddison Eddy, Lucy McLeod and Callum Knauf

Assistant Editor: Jamie Hodgson

Edited at: Work Post

Colourist: Tom Balkwill

Visual Effects: Jorge Canada Escorihuela

Online Editor: Gareth Bishop

Confirmed at: Dirty Looks

Production Assistants: Andrew Orr, Samantha Holmans

Archive: Dementia 13 (1963) Directed by Francis Coppolla

With Thanks: Maddermarket Theatre Costume Department, Onsight, Panalux, Walpole Bay Hotel, The Belle Vue Tavern, The Lifeboat

A PRODUCTION BY THE NOTHING

COPYRIGHT: 4AD / GLASSNOTE 2015